The medieval setting has become almost synonymous with the fantasy genre (to the dismay of some), and there are no greater features on a medieval landscape than that of castles and keeps, walled cities and impregnable fortresses. When writing about such things it’s crucial to understand them and how they work so as to avoid any flaws in your storytelling. But better still, understanding them will make your stories shine.

In our first assault, we tackled a few of the main types of fortification found in castles—towers, gatehouses, moats, drawbridges—as well as looking at some of the earlier types of medieval fortifications. Today we’re going in for a second charge to tackle walls, battlements, and the structures within the walls.

Walls

The phrase enceinte is the technical term for the walls and towers that encircled a fortification (it’s also an archaic word for pregnant, so careful not to confuse the two!). The walls were also referred to as curtain walls.

Walls developed significantly during the Middle Ages. One of the earliest types of wall was a dense structure made of earth and wood. Timber walls soon replaced these, though they were thin, vulnerable to fire, and over time, decayed. The solution to such problems came in the form of stone walls, though early stone walls were pretty thin.

The Roman method of building walls was much superior. They built two walls with a space in between which they filled with rubble. Despite Roman walls surviving into the Middle Ages, nobody thought to copy them. Arrogance, perhaps? Maybe ignorance?

So how big were walls? It’s hard to say. Few records were kept of the constructions of walls, so what’s known today is the result of archaeology and guestimates. We can turn again to the Romans who had a pretty good system for making walls. For every one meter of height, there had to be 0.25 meters width. So, for example, a wall 6 meters high would be 1.5 meters thick. But it all depended on how thick the walls needed to be. Vulnerable sections of wall were built the thickest, whereas those upon favourable terrains, such as hills, were thinner.

Towers became a staple feature of walls, ranging in height from 10 meters to as tall as 37 meters. Toward the end of the Middles Ages, the height of some walls was raised to the height of towers. Staircases inside towers and battlements turned clockwise to allow for the defenders to fight with their right hand and restricting the swing of any attacker.

Keeps were pretty imposing too, and over the years grew in size. Large keeps were 20 to 30 meters by 15 to 25 meters, with walls 2 to 4 meters thick. The castle at Coucy, France is particularly large, and in Angers, France, there lies another immense fort. The French got carried away a bit, it seemed.

Battlements

The term battlement refers to the upper part of a wall. During the Middle Ages, they usually featured crenels (an indentation in the battlements), embrasures (an opening in a wall or parapet) and merlons (the solid part of a crenellated parapet between two embrasures).

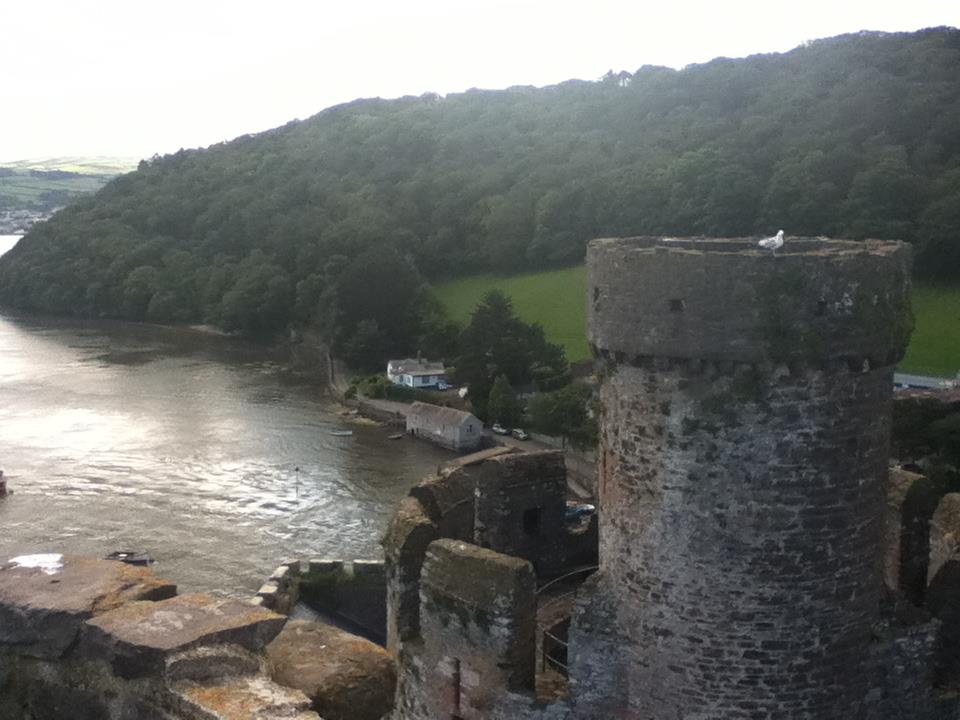

A picture I took at Conwy Castle, Wales. At the bottom, next to the tower, you can see examples of merlons.

Melons were not always rectangular in shape. In time they became more decorative, the style influenced by region and culture. In the Middle-East for example, the shape of merlons was influenced by Islam.

The space in between the merlons sometimes featured shutters to provide extra protection. This did, however, restrict the archer’s range of fire to what was beneath them. As the skills of masons developed, such shutters became redundant. Instead, slits were carved into the stone, known as an arrow loop, through which arrows could be fired. At first, they were thin, restricting the scope of fire to one direction, but they developed with time with wedge-shaped variations developed. This restricted the archer’s view to what was beneath them but reduced the scope of vulnerability. A cross-shaped loop was developed too which allowed for sight left and right. A feature called an oillet, which is a small circular observation hole, was also added.

Here’s me at Conwy Castle, Wales, re-enacting a defender. And to the right is an example of an arrow loop.

Behind the crenels was the wall walk, also known as an allure. In some castles they were built into the walls, in others they were wooden, supported by beams. Towers, which often were incorporated into the battlements, also had allures, giving defenders greater height with which to observe the battle and target threats. Towers with no allures had roofs of slate or lead, conical in shape.

To get up and down the allures two options were preferred: the bog standard ladder, and a stairway within a wall tower. The latter was more effective defensively. If attackers swarmed upon the walls, they were trapped there, exposed, unless they managed to take a tower.

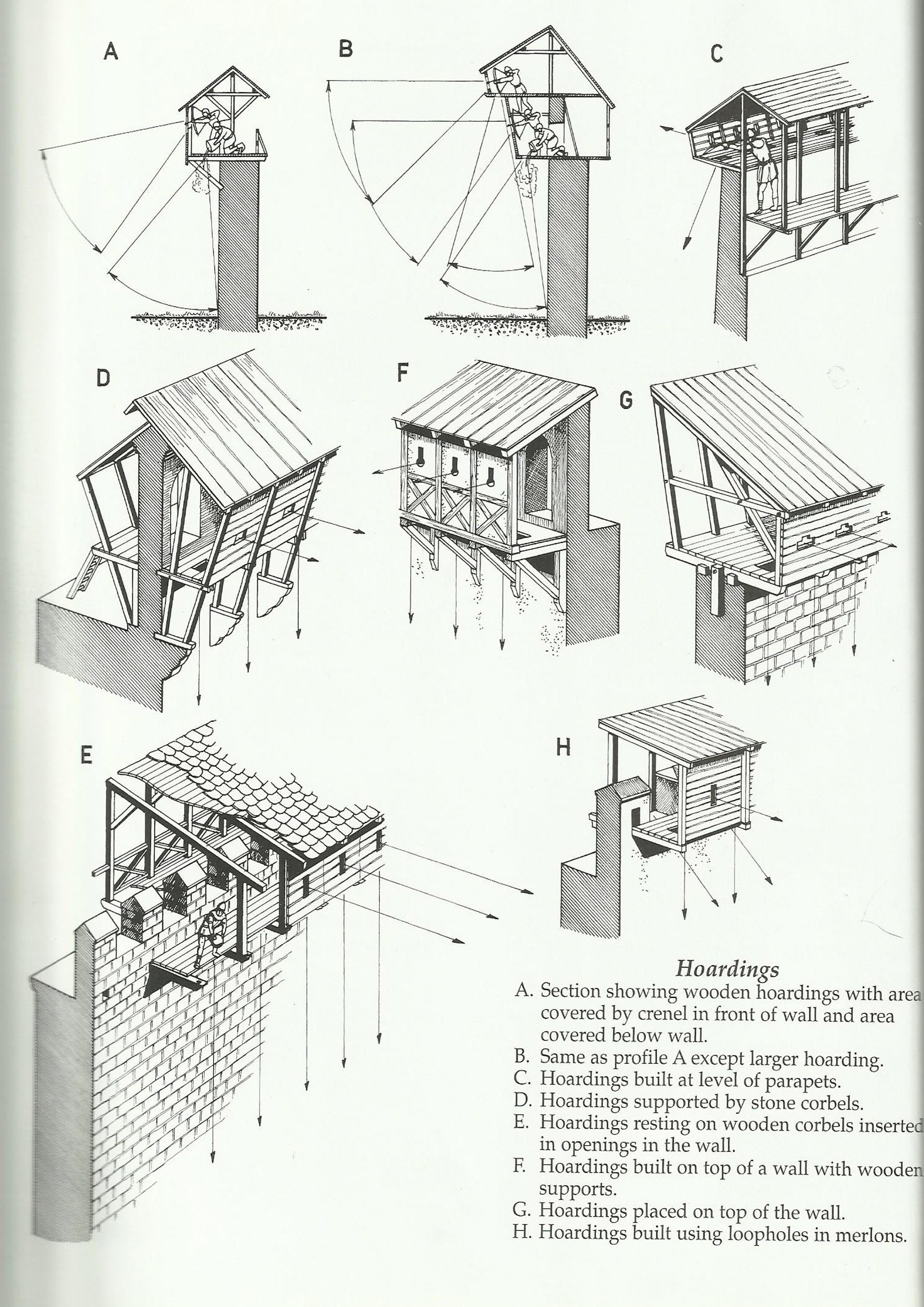

To aid the defenders further, in or around the 12th century a feature known as hoardings was introduced. They were wooden structures which projected out over the wall, sort of like scaffolding. How did they do this, you wonder? During the construction of the battlements, slots or holes were added to allow for beams to be fitted. They were vulnerable to fire, but to counter this their roofs were covered with wet hide.

Image is taken from ‘The Medieval Fortress’ by J.E. Kaufmann & H.W. Kaufmann.

As you can see in the above drawing, the range of fire is much greater upon the hoardings. Rocks and scorching liquids could be dropped on the attackers below. Some walls featured a plinth at the bottom, which was a section of wall which jutted outwards. Rocks bounced off of these plinths and into attackers, extending their effectiveness.

Hoardings were later incorporated into the walls. Parapets, supported by arches, were moved forward to hang over the walls and in that additional space something called a machicolation was introduced: essentially a hole in the floor.

Windows were a rare feature on towers and walls and even keeps. They were seen as weak points. Only the residential towers or keeps had windows, which were made from glass, normal or stained, or just iron bars (glass was expensive).

Inside the walls

Image is taken from ‘The Medieval Fortress’ by J.E. Kaufmann & H.W. Kaufmann.

What did the defenders need to sustain a siege? An important feature was wells. Rainwater could be gathered too, but without a supply of water, defenders couldn’t last long. Water was also vital to helping douse any fires caused by attacks.

Residential areas were usually found in a keep or tower. Inside was a great hall or banqueting room, bedrooms, garderobe (toilet), storage rooms, and so on. The kitchen was kept separate due to the risk of fire.

A classic feature of the great hall is a huge hearth. It wasn’t until the 14th century that chimneys were introduced, so up until that time people were exposed to toxic fumes.

Hearth at Tattershall Castle, London

Walls were decorated with tapestries, which provided a mild degree of insulation. With few windows, illumination came from torches held in sconces and candles.

The courtyard, or bailey, was the main open area within a castle. Some larger castles had more than one courtyard. Other buildings you’d find within a castle were a chapel, stables, and barracks. Castles did not have dungeons during the Middle Ages. Prisoners were kept in towers; only in the Renaissance period were prisoners moved to the pits of the castle.

Medieval Fantasy Castles

So we’ve taken a look at the different components that go into making the ultimate defensive fortification. Now it’s time to think of ideas. And I don’t know about you, but looking at pictures and artwork doesn’t half get the juices flowing.

So in this section, I’ve included some pictures of medieval fantasy castles. And to find more, just head over to Pinterest.

More Guides and Resources On Medieval Fantasy Castles

Thank you for reading this guide to medieval fantasy castles. I hope you’ve found it useful. Below, I’ve included links to some other guides you may find useful, all related to fantasy writing and worldbuilding.

- Click here to read part one of this guide to medieval fantasy castles

- Or click here to find out about fantasy archery

- A complete guide to worldbuilding, with a template

- A guide to medieval weapons

- Medieval armor and the fantasy genre

- The lives of medieval lords

- How were women treated in the Middle Ages?

- The lives of peasants in the medieval period

- A complete guide to medieval cannons

- Siege warfare

- Roman battle tactics

- How to build a fantasy world

- Worldbuilding in fantasy

- 5 Tips to Help Your Child Learn and Succeed at Primary School - February 26, 2024

- The Advantages Of Using An AI Essay Typer Alternative - February 14, 2024

- Advice On Getting Help With Your Homework - January 26, 2024

This is a fantastic article for any fantasy writer! I wish there was some way for me to save it lol

Thank you, Kayla! I’m delighted you found it useful. The trusty bookmark never fails!

Oooo how do I do that? I’m new to Wordpress

It’s a little feature on your browser. What are you using? I think Chrome and Firefox have a little star near the top. Click that on a page and it’ll save it for you

Thank you!

Love the “inside the castle” diagram you posted at the end there. Such diagrams are so useful. But I’ve had to catch myself from going too deep with formal terminology. How many fantasy readers are going to know what a “covered allure” is? Heck, I didn’t before seeing the graphic. Same thing goes for armor or other things that have a lot of, what is essentially jargon now. Unless you’re writing a story about a kid who is obsessed with proper castle descriptions… “Excuse me, that is no mere balcony friend. That is a breteche!”

Hahaha. I can’t imagine many men shouting “To the enceinte!” either. Like you say, certain characters could use fancy words like allure, but for the reader’s sake wall wall walk is sweet

“Secure the machicoulis!” — “What the hell are you talking about , Bob?”

“They’re ascending the plinth!”

“The what?”

Pingback: A Fantasy Writer’s Guide to … Castles and Keeps: Part I – Richie Billing

Pssst… “Enceinte” is modern French. Hardly “archaic.”

Pingback: The Siege – Richie Billing

Pingback: Design 2: Pre-Production – Project ideas and moodboards – Michael Woods

Thanks for sharing!

Pingback: The Siege - Richie Billing

Pingback: How To Create A Fantasy Castle | Richie Billing

Pingback: The Medieval Lord - The Complete Guide | Richie Billing