Medieval cannons changed European warfare forever. In a short space of time, this alien contraption that could make sounds people had only ever heard come from the sky was introduced.

Able to fire great medieval stone cannon balls, they could take down walls, sink ships and instil fear in the hearts of warriors.

But things weren’t all plain sailing for the medieval cannon. It took years for the science behind its functionality to be perfected, and as we’ll see below, this made them quite ineffective and, at times, counter-productive.

A Guide To Medieval Cannons

The intention of this post is to help you out with some worldbuilding research that you can use to help inspire your own stories. It looks at the development of European medieval cannons, how they were made, the gunpowder used, and how they fared in battle.

If you have any questions provoked by this guide, please don’t hesitate to get in contact, or alternatively, join my online writing group, the details of which you can find below.

Were There Cannons In Medieval Times?

Many people believe that cannons weren’t invented until much later on in the Middle Ages. However, there’s an account of the first cannon being used in 1260 by the Mamluks in their war with the Mongols.[i]

In Europe however, the first reliable reference to medieval cannons comes from Florence in 1326, where brass cannons and iron balls were ordered to aid the defence of the city.[ii]

By the 1340s they seem to be more common. The official accounts of the city of Lille record a payment for “three tubes of thunder and one hundred arrows.”[iii]

As we’ll see, these early cannons were far from perfect and mostly ineffective, but they struck fear into the hearts of men and changed the nature of warfare forever.

How Did They Make Medieval Cannons?

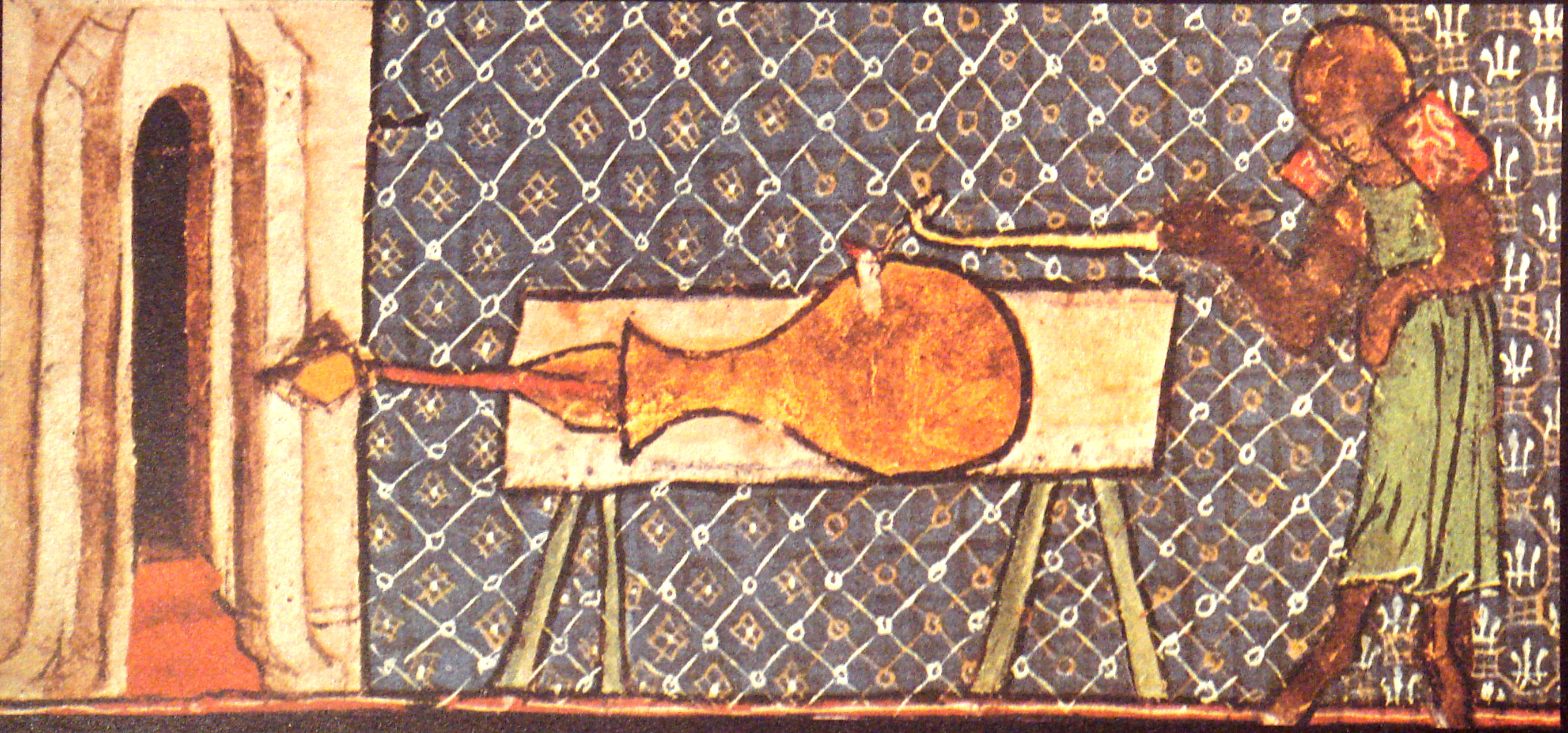

The earliest depiction of a European medieval cannon can be found in a treatise on kingship, ‘De nobilitatibus sapientii et prudentiis regum’—catchy title—written in 1326 by English scholar, Walter de Milemete.

The medieval cannon was made of cast iron or bronze (both were used in the early days) using similar techniques to how they made bells. These early cannons weren’t very big—historians estimate about three feet in length—with the bottleneck end wide enough to hold the shaft of an arrow.[iv]

To ignite medieval cannons, a hot iron was held to a trail of powder which fed into the bowl-shaped chamber and then to the charge.

These early cannons had various names. Pot-de-fer was one such name, which in French means iron pot. In Italy, it was known as the vasi, which means vase.[v]

You may have noticed that it’s just lying on a table. Early cannons had no carts or wheeled platforms. Forget about aiming. With nothing to hold it down, the cannon would have shot up into the air upon firing, sending projectiles in indiscriminate directions. But they’d cracked the method. It just needed improving.

Medieval Stone Cannon Balls And Other Projectiles

Of course, being able to shoot projectiles out of a tube was all well and good; much depended on what it was they were actually firing.

Medieval stone cannon balls were a popular projectile, namely because they were cheap and easy to get hold of, and being heavy they also did a good bit of damage, but didn’t travel as far.

As you can see in the image below, they were pretty sizable, bigger than a fist and round and smooth. Size depended upon how big the cannonball was.

As time went on the designs of cannon balls changed. Soon stone was replaced with iron, with hollow balls filled with gunpowder produced to deal more deadly and explosive blows.

How Did Early Medieval Cannons Fare In Battle?

As with any new toy, those who had cannons were keen to use them. In 1346 French historian, Francois Mezeray, noted in his account of the Battle of Crecy that King Edward “struck terror into the French Army with five or six pieces of cannon, it being the first time they had seen such thundering machines.”

Medieval cannons were rolled in along the flank to falter the charge of the French cavalry.[vi] The 6,000 Genoese crossbowmen, hired by the French, were rattled by the explosions and fired their bolts before they were in range of the English line.[vii]

The English took advantage and unleashed incessant volleys with their longbows, butchering the French and sealing victory.

But the cannons did little if any damage. They were more of a showpiece and caused more problems than they were worth.

Everyone loves a scapegoat, and the blame was placed at the door of the crafting process. Casting was a demanding and costly method requiring skilled craftsmen, and there weren’t many about. So a new method was sought.[viii]

Revising The Design Of Medieval Cannons

Nearly 643 years ago, Jehan le Mercier, a Counselor to the King of France, was instructed to organise the manufacture of ‘un grand canon de fer.’ “A big fucking cannon.” Not really. It translates to “a big iron cannon”. The vase shape was abandoned and a more cylindrical one was sought.

With casting forgotten, the barrel of the cannon was built from longitudinal strips of iron which were welded together with heat and hammer. They were then secured with iron rings which were heated and passed over the tube to keep the shape rigid. Ninety pounds of rope was then wrapped around it to give even more solidity. Lastly, hides were used as a covering to protect from dampness and rain.[ix]

This new design proved far superior: more accurate, powerful, and reliable. For an example we can look back to 1377. Philip the Bold, Duke of Burgundy, commissioned the construction of a monster cannon, one which could fire a ball weighing forty hundred and fifty pounds. It was reported to have taken nine men nine days to build and was tested at the Siege of Odruik. How did it fare? Medieval author, Jean Froissart, reveals all:

“The castle of Odruik was situated on a motte, surrounded by a ditch filled with very large spikes … The Duke of Burgundy set up his cannons and fired maybe five or six quarrels in order to provoke surrender. Three quarrels were such that, because of the power of the discharge, they penetrated the walls.”[x]

The key detail we can take from Froissart’s account is the ‘power of the discharge.’ And this leads us to gunpowder.

Gunpowder

The ingredients of the gunpowder used with medieval cannons were:

- 41% Saltpetre

- 29.5% Sulfur

- 29.5% Charcoal

These ingredients were ground down into a fine powder and mixed together. This mix was tossed into the cannon with little to keep it together. It invariably led to irregular ignitions and fires continuing after the explosion.

Much gunpowder was wasted which those with coin didn’t like. Saltpetre was scarce meaning the price was high—twice that of iron.[xi]

There was another problem too. When transported the mixed powders unmixed themselves. Being heavier, saltpetre and sulfur shuffled to the bottom of the barrel, leaving charcoal sitting on the top. This meant it had to be mixed at the cannon, causing delays, and presented the risk of friction ignitions. Careless hands could see them blown off.[xii]

In the early fifteenth century, some clever bastard came up with a solution: ‘corning’. The mixing process was altered so instead the powders were wetted to make a paste. This was then spread out into a thin cake and left to dry. It was a game-changer. The ingredients held together, it was easier to transport, easier to load into medieval cannons, and above all, led to more consistent, faster, and violent explosions.[xiii]

Another Problem With Cannons?

Nothing’s ever straightforward, is it? The much-improved gunpowder proved too powerful for the cannons. The explosions within practically blew them into the pieces that assembled it.

But a solution was at hand: revert to the past. By the middle of the fifteenth century, casting was being used again to make cannons. The solid form gave more stability and strength to house the violent explosions within.[xiv]

But still, the cannon wasn’t perfect. The last problem was its mobility.

Making Medieval Cannons Mobile

Before someone thought to stick it on wheels, medieval cannons were laid out on tables or platforms or even just the floor—a detail I use in my debut novel, Pariah’s Lament, which features cannons in their infancy.

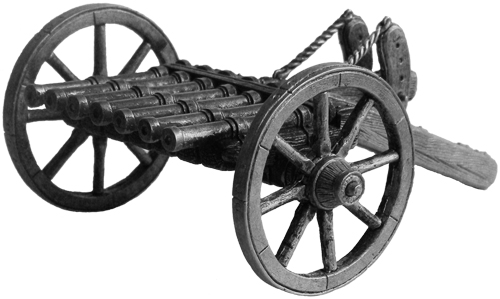

One of the first wheeled artillery machines cropped up around the end of the fourteenth century. It was known as ‘the organ gun’.

As you can see from this contemporary version, it holds similarities to the church organ, which is why it got its name. These smaller barrels could cover a broader stretch of the battlefield, spraying infantry or cavalry and faltering lines. This is also quite similar in design to the medieval swivel cannon, able to turn quickly.

It wasn’t as effective as it sounds, but one thing it did have was wheels. It was placed upon a two-wheeled cart and could quickly move positions on the battlefield.[xv]

Within the space of about 200 years, the Europeans hook great strides toward mastering the art of the cannon. They discovered the three basic requirements: cast forged guns, a reliable and powerful propellant, and mobility, a formula that continued to be used for centuries after.

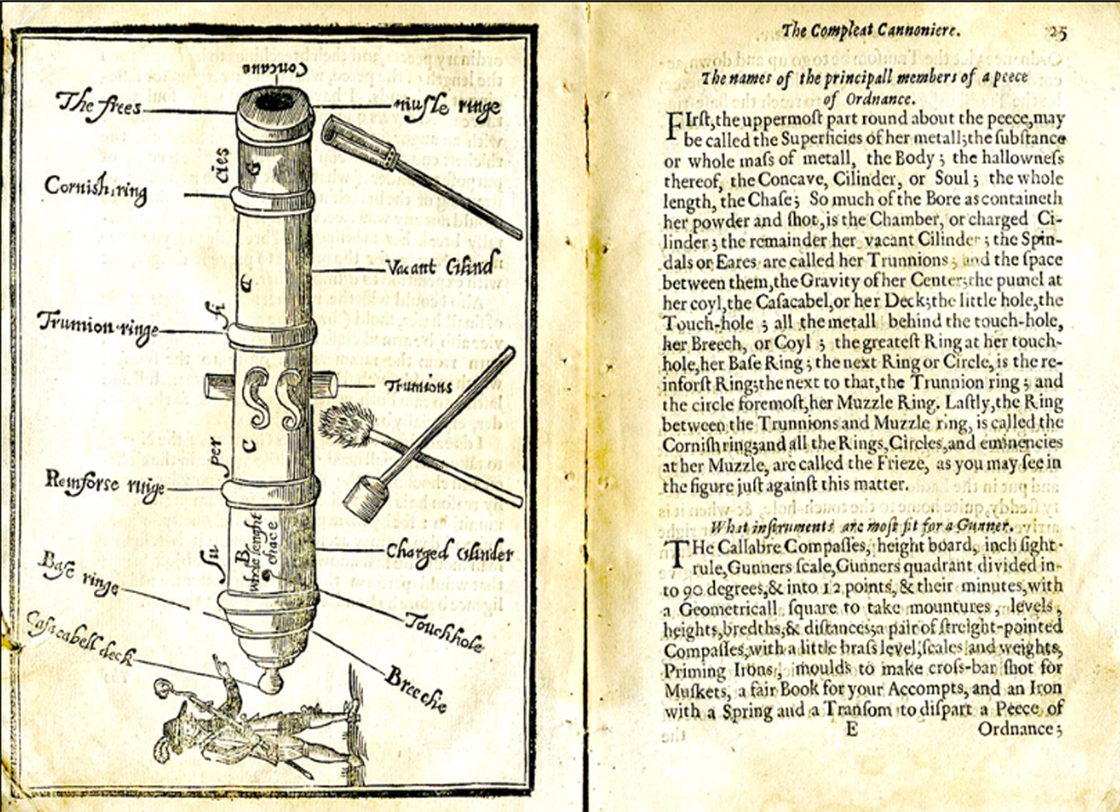

The Anatomy Of A Medieval Cannon

It always helps to have everything laid out for you in a nice simple anatomised way. This is particularly true when it comes to looking at bows and arrows, armor and other types of medieval weaponry.

Once the design of the cannon was cracked, it was used and relied dupon for hundreds of years, with little divergence. It did, however, lead to bigger and more powerful medieval cannons being produced.

If you’re wondering what the largest medieval cannon was, take a look at this:

This behemoth is called Mons Meg and sits at the top of Edinburgh castle. Just look at the size of those stone balls. With such power, a cannon like this could smash through castle walls, which ultimately led to the fall of the medieval castle.

When Was The First Cannon Made?

The first cannon was invented in China around the 12th and 13 centuries.

With the invention of gunpowder, cannons quickly became popular. Their use spread to Europe and throughout the 13th-century cannons featured on medieval battlefields. It spurred the development of the European cannon, which led to creations such as Mons Meg.

More Guides On Medieval History and Fantasy Worldbuilding

With such a significant influence on the genre, it’s very much worthwhile taking a look at medieval history and learning what you can. It all serves the purpose of helping to inspire your own fantasy writing, so trust me, it’s worth it.

Below, I’ve included some guides to save you the trouble of doing that research.

- A complete guide to worldbuilding, with a template

- A guide to medieval weapons

- Medieval armor and the fantasy genre

- The lives of medieval lords

- How were women treated in the Middle Ages?

- The lives of peasants in the medieval period

- A guide to medieval castles

- Siege warfare

- Roman battle tactics

- How to build a fantasy world

- Worldbuilding in fantasy

And to learn more about the development of gunpowder weapons, check out this guide from Southampton University.

This guide from St Andrews University also has great information on medieval stone cannon balls, guns and gunpowder in the late Middle Ages.

References

[i] (https://www.historychannel.com.au/this-day-in-history/first-cannon-fired-in-battle-maybe/)

[ii]Pg. 201, H.W. Koch, ‘Medieval Warfare’

[iii]Pg. 202, H.W. Koch, ‘Medieval Warfare’

[iv]Pg. 203, H.W. Koch, ‘Medieval Warfare’

[v] Pg. 204 H.W. Koch, ‘Medieval Warfare’

[vi](https://www.britishbattles.com/one-hundred-years-war/battle-of-crecy/)

[vii](https://www.historychannel.com.au/this-day-in-history/first-cannon-fired-in-battle-maybe/)

[viii]Pg. 205, H.W. Koch, ‘Medieval Warfare’

[ix]Pg. 206, H.W. Koch, ‘Medieval Warfare’

[x] Pg. 59, ‘The Artillery of the Dukes of Burgundy 1363 – 1477’ R.D. Smith and K. De Vries.

[xi]Pg. 206, H.W. Koch, ‘Medieval Warfare’

[xii]Pg. 206, H.W. Koch, ‘Medieval Warfare’

[xiii]Pg. 207, H.W. Koch, ‘Medieval Warfare’

[xiv]Pg. 208, H.W. Koch, ‘Medieval Warfare’

[xv](https://www.thevintagenews.com/2016/12/06/the-ribauldequin-medieval-machine-gun-considered-as-the-predecessor-of-the-19-th-century-mitrailleuse/)

If you have any questions at all about this guide to medieval cannons and how you can apply it to your novels and stories, comment below or get in contact.

- 5 Tips to Help Your Child Learn and Succeed at Primary School - February 26, 2024

- The Advantages Of Using An AI Essay Typer Alternative - February 14, 2024

- Advice On Getting Help With Your Homework - January 26, 2024

Fun. I just added a scene dealing with cannons to one of my fantasy stories. More background elements, but there. 😀

Pingback: No Wasted Ink Writers Links | No Wasted Ink

Thanks for sharing!

Pingback: A Guide To Siege Warfare - Richie Billing

Pingback: The Lives of Women During the Middle Ages - Richie Billing

Pingback: The Lives Of Medieval Peasants - Richie Billing

Pingback: Roman Battle Tactics - Richie Billing