Welcome to this guide on how to create fantasy languages. Some of the greatest authors in the fantasy genre, Tolkien in particular, invest a huge amount of time in worldbuilding, with the creation of a fantasy language sometimes playing a big part in that.

Writing fantasy can so often leave you caught up in a web of your own making. Most fantasy involves a secondary world, that is a world different from our own. Granted, it doesn’t have to be totally original, but it raises the question: how different should we make it? Should we scrap everything we know and play God and build from scratch? Should we shape and morph things that already exist? Or should we keep what everyone finds familiar?

These questions can be asked when it comes to inventing anything for our worlds, but one such area in which it’s particularly prevalent is with language. In this new world of ours, does everyone speak the same language?

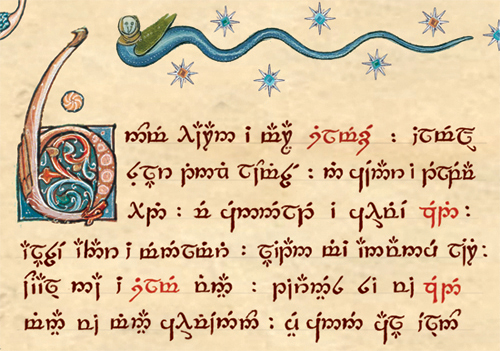

Let’s look at Lord of the Rings. Every race had their own language—Tolkien was a big believer in developing language, a way of giving greater identity to each race. But do we all have to go to the same lengths as Tolkien? Is that style of world-building even still relevant to the modern day reader? Questions not easily answered. Since you’re here, let’s assume you do want to make a language. How the hell do you go about it?

To help make things clearer, I’m delighted to welcome the excellent writer Helen Gould, who’s written a fine piece on her experience of creating her own language for her novel, Floodtide. Enjoy!

I hadn’t intended to invent a language for Floodtide when I started writing it, and it wasn’t until a later draft that there was one. But several things convinced me that I should introduce one.

In the later parts of the story, where there are interactions between the main hero, Jordas, and the tribes, he learns of various traditions common to both the Sargussi and the Shiranu tribes. One of these is the idea of status-debt: that if you did something wrong to someone else you would owe them some of whatever status you’d accrued within the tribe prior to that time. In a woman’s case, she might have borne one or more daughters – because there’s a shortage of females within the tribes. A man might show great courage or physical strength, or help other tribal members. I didn’t have a name for this concept, or several others that could only be expressed in English as compound nouns, as in ‘status-debt’, or not at all. However, status-debt is a concept that it’s vital for the reader to grasp, as it’s how the tribes ensure good behaviour.

Around the time that I was writing the first draft of the novel, my husband Mike and I were invited by Carol-Ann Green, who was at the time the Orbiters Co-ordinator for the British Science Fiction Association (BSFA), to join the Hull Writers group, then based at Hull University where she’d been a student. We spent Saturday morning working on world-building in small groups, and in the afternoon wrote stories set in the world and societies we’d invented. The following day we did writing exercises in the morning. In the afternoon we workshopped personal projects; I worked on Floodtide.

One of the things she said, when we got to the bit where Yado has had his circumcision with the ceremonial obsidian knife and met Soolkah whilst on his initiation quest, was that whenever she read ‘his organ’ or some similar phrase it made her think of church organs. Apart from setting me chuckling, this made me think about how we describe the anatomical parts of our heroes’ bodies in sexual situations. (At university I was always amused by geologists referring to rock sequences as, e.g., the Peterborough member’!)

This led me to introduce a Naxadan language. It doesn’t have a written form, but it’s common to both tribes. I felt I was well-qualified to come up with such a thing as I’d studied French and German to A level at school. I’d also learned Latin at my previous school, and had worked as a Translations Assistant in my first job. I’d dabbled in various other languages, including learning Russian for a year – until my teacher had returned to Poland – and I’d learned Urdu for three years for my job at the time. I understood grammar well and had also taught ESOL students English for 3+ years, important in this context because it had given me an awareness of word families, on which much of the Naxadan language is based. So I began developing the Naxadan language.

Like many other people of my age, I don’t remember learning much English grammar, just the usual parts of speech like nouns, verbs and adjectives; but grammar is largely similar in many European languages, since they all derive from Indo-Iranian, so the grammar I know is a bit of a hotch-potch of English, French, German, and Latin grammar. I also had a brilliant Latin teacher, Mr Thomas, who taught us how to work out where words originated. And it works as a basis for using the language to write, and if I need to I’m more than capable of looking up anything I need to.

And as I worked, it became important to me to build in the extra idea that men and women in the tribes would have their own words for their own and each other’s ‘naughty bits’ – which they’d share with each other, but not the opposite sex. I guess this is an extension of what happens in English with some words – but taken to an extreme, so that sharing them with the opposite sex was forbidden, not just frowned on. And it got over that awkwardness around mentioning the more private body parts.

The full notes on the Naxadan language and its pronunciation that I developed are available as a glossary on my website, www.Zarduth.com, but I also explained them in the text of Floodtide, since I knew that some readers dislike having to refer to the front or back of a book as they go along. Take a look. It might give you some ideas. In the meantime, here are a few examples to tickle your reading palate!

Amaaj: Family group. In the Sargussi and Shiranu tribes, these consist of brothers, who are telepathically linked, their wife (they practice fraternal polyandry due to a shortage of females in the tribes) and their children.

Gare (pronounced ‘gar-eh’): brother.

Maaj’gar: ‘thought brother’ – refers to the fact that in each family group, all the brothers are telepathically linked. Women aren’t telepathically linked, though. The most basic level of linkage is the sharing of sense impressions, which cannot be shut off. Telepathic communication and the sharing of information are the other levels, and they do require a bit of effort. Brothers can also use the privacy shield to shut out unwanted contact.

Helen Gould is a science fiction writer from Peterbrough, UK. Floodtide is her first published novel, but she has several more novels and short stories penned too, most of which are set in her own fictional universe. You can follow Helen by clicking the links below:

Thank you, Helen, for the fantastic insights into the process. It’s one thing to have the idea of coming up with a different language and another thing to create it. You may not find yourself in Helen’s position in which she already knew a lot about languages, but there’s nothing to stop you from learning. With the world as small as it is nowadays, I’m sure you can find some talented bilingual person to give you some guidance, if indeed that’s the path you want to take to develop your language. You could take another approach altogether and head down the hieroglyphic route, or develop a series of symbols to replace letters. The possibilities are endless!

What are your own experiences of using languages in fantasy, or any genre for that matter? Have you gone into Tolkien-esque detail or have you veered clear?

Thanks for reading this guide on fantasy languages. If you enjoyed it, why not stay in touch by filling out the form below. Everyone who subscribes receives a free ebook on the craft of writing, lists of publishers for short and long fantasy fiction, two free short stories, and a list of book reviewers. I usually send a newsletter once a week with links to articles I think may be of interest too.

- 5 Tips to Help Your Child Learn and Succeed at Primary School - February 26, 2024

- The Advantages Of Using An AI Essay Typer Alternative - February 14, 2024

- Advice On Getting Help With Your Homework - January 26, 2024

Great share. Didn’t Tolkien start by inventing the elvish language and only after decide he should write a story about it? 😀

Interesting post and some good info too.